Earlier this year I wrote about a case where the court did not allow an extension of the “limitation period” (the time limit for bringing court proceedings) to enable a survivor of abuse to take a claim forward, click here to read my previous blog.

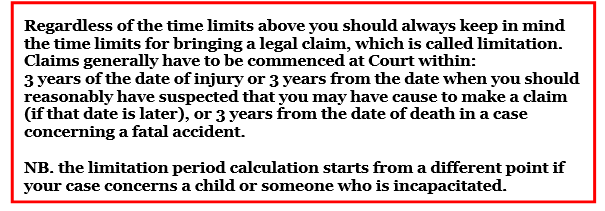

Generally, there is a 3 year period from the date of the event or, in the case of a child, from the age of 18, in which a claim for injuries caused by negligence can be brought at court. The period is different if a claim is directed at the person who did the abusing (an assault type issue). In cases against an employer or organisation which was negligent in not preventing the abuse, there is a general assumption that the court will exercise a discretion to extend that time and to waive the period. However, another very recent case, Archbishop Michael George Bowen -v- JL suggests that the courts are getting less lenient in attitude.

This was a case where in fact the trial judge had exercised his discretion in favour of the claimant. However, the defendant decided to appeal the decision. It went to the Court of Appeal and the Court of Appeal’s decision was that the trial judge had failed to take into account the full extent of the delay and the considerable prejudice caused by it.

In this particular instance, the claimant alleged that he had been abused by a Father Laundy for a period of 10 years leading up to 1999. The claim was commenced in 2011. The limitation period had long since expired.

The circumstances of the case were that Father Laundy was a Catholic priest and the chaplain of a scouts group attended by the claimant. The archbishop was a nominal defendant, that is that he had been in the post of archbishop of the area at the time.

The first issues in relation to sexual assault appear to have arisen when the claimant was approaching 17. The alleged abuse continued over a decade or so.

Father Laundy was subsequently arrested in connection with allegations of sexual assault concerning other individuals. There was a criminal charge. Father Laundy was convicted of criminal acts in relation to the claimant. He could have defended those but he chose not to do so. He did however indicate that any sexual relationship with the claimant was by consent. Much of the activity was after the legal age of consent and it was unclear what incidences may have taken place before the age of 16.

Normally a claimant would feel quite safe in relying on criminal convictions to provide evidence for a civil/compensation claim. This does not however prevent a defendant from challenging this particularly if the defendant is not the perpetrator but an employer.

The convictions were indeed subsequently relied upon by the claimant, understandably, in the civil proceedings. This meant that in order to defend the civil proceedings, effectively the archbishop’s legal team had to establish that Father Laundy had proceeded with consent. However, Father Laundy had died.

The civil proceedings claimed that the abuse had gone on for a lengthy period and had commenced when the claimant was only 13. Information about the original conviction seemed to be fairly minimal.

The limitation period

A claim of this kind has a three year period. This dates from the age that somebody becomes an adult or as an adult, three years from the date of an event generally. There are some exceptions.

For whatever reason and clearly the claimant had his own difficulties, despite the criminal trial, he did not take the claim forward for many years. Father Laundy was convicted in 2000. The claimant consulted solicitors in December 2010 and proceedings were issued in November 2011.

The court have to take into its consideration how a defendant is to be able to defend after a long passage of time. The general assumption has always been that the court will tend to exercise its discretion because many of the claimants who have suffered abuse, have their own difficulties as a result and find it not an easy process to come forward and deal with matters.

In this case, however, the court felt that the delay was too significant. The delay was not the period from 2000 to 2011 which would, in itself, have been far in excess of the limitation period. These events were taking place between 1989 to 1999.

The view of the court was that the question of consent was at the very heart of the defence and had some minimal support from previous evidence provided by Father Laundy. There was certainly an arguable case that the sexual activity was to a large extent consensual. In any event, Father Laundy was not around to be cross-examined at trial. The court was deprived of his evidence which was fundamental to whether the case could proceed or not.

There were also some criticisms of the claimant in relation to the evidence that he provided.

Taking those issues aside, this was, in essence, something which a solicitor would ordinarily think a reasonable case to take forward. There were criminal convictions on file for the same offences. However, the case was dismissed by the Court of Appeal on the basis that the length of time was too long; that the claimant himself had some difficulties as a witness but, more importantly, the perpetrator of the crimes was dead and his evidence previously had indicated consent.

These are factors which occur significantly in abuse cases and this is a case which presents claimants’ solicitors perhaps with difficulties taking cases forward. If you have been suffered abuse, the advice always has to be that if you wish to pursue a claim, please see a solicitor as soon as possible.

It is important however for survivors of abuse and claimants’ solicitors to recognise that there is a distinct shift in the approach of the courts and they are now much less generous in their approach to claimants.